Disclaimer: Editor’s opinions are also stated with scientific facts in the following article. Reader’s discretion is advised. Follow public health guidelines to keep everyone safe!

What is monkey pox: in a nutshell

Monkey pox virus is a close relative to the small pox virus that causes rare pox-like illness in humans and can be fatal in many cases. It is identified with a characteristic fluid-filled blister formation on skin combined with fever, headaches and swollen lymph nodes among other symptoms.

Monkey pox usually develops within 7 to 17 days after exposure to the virus and blisters tend to form within two weeks. Evidently monkey pox virus has the ability to jump between different animals such as rats, squirrels, monkeys and humans which made its eradication very difficult.

At the moment monkey pox infection can be definitively diagnosed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), similar technique used in initial diagnosis of Covid-19. There are other diagnostic tests such as antigen and antibody testing, but are not very reliable as they are not specific to monkey pox.

There is no specific treatment for monkey pox but anti-viral drugs used to treat other viral diseases such as Cidofovir or brincidofovir may be used in severe cases. However, these drugs are not approved by any regulatory authority for use against Monkey pox as of this date.

How did it get into Humans

Monkey pox virus has gained attention recently with new cases in the western world, however it has existed alongside smallpox for thousands of years. Since it is clinically indistinguishable from other pox-like diseases, it was never under scrutiny until the eradication of small pox.

Monkey pox is presumed to have emerged in sub-Saharan Africa with the first case reported in 1970 from Democratic republic of Congo. It is still unclear on how the virus jumped from the animals and it is difficult to point to the exact source of the infections.

Human-to-human transmission of the disease is possible, particularly in people who are not vaccinated against small pox but is very inefficient compared to the small pox. It can be transmitted via respiratory droplets like Covid-19, infected personal items like clothes or utensils (called fomites) and direct contact with infected person. It is presumed that rodent infestations and hunting and consuming infected meat of wild animals has high probability of causing the infection. The source of the recent 2003 USA outbreaks was traced back to an infected shipment of wild rodents from Ghana.

Is it possible for monkey pox to be pandemic?

After Covid-19 pandemic and associated disasters, recent emergence of monkey pox cases have stirred fear in masses over the next pandemic. Unlike Small pox, Monkey pox virus has a wide range of host animals to survive (a.k.a animal reservoirs) and it is not possible to completely eradicate the virus.

The ability of a virus to directly infect others from one infected person is known as Basic reproduction number or ‘R’ number. For reference, Omicron BA.2, the highly infectious variant of Covid-19 has an R number of 12, while the monkey pox was recently calculated to be 2.13. Given that the monkey pox infection can be transmitted through respiratory droplets similar to the Covid-19, it is theoretically possible for the infection to spread in a quick pace.

On the brighter side, small pox vaccines have shown to be very effective in the prevention of Monkey pox. People vaccinated against small pox have less chance of developing a serious disease if exposed to the pathogen.

However, we also have to take into account the many variables that will spread the virus rapidly like:

1) The mutation of the virus as it spreads,

2) Effectiveness of smallpox vaccine received several years ago,

3) Ineffective control measures to prevent spread of infection

4) Arising conspiracies in masses and non-compliance to health care guidelines

In short we do not have a definitive answer as of this date, since there are very few cases, the data is not enough to suggest that monkey pox may or may not be the next pandemic.

Finally, if you were already vaccinated against small pox as a child, you probably safe against monkey pox too!

You do not have to sit at home, wait for scientists to develop drugs and vaccines and then insult them with strange conspiracy theories and anti-vaxxer propaganda (you missed your chance here!).

What can we do to stop its spread?

Firstly, we should avoid contact with infected people when and where ever possible. Though it seems like a no-brainer, you will be shocked to know how many people in the world cannot understand a simple concept.

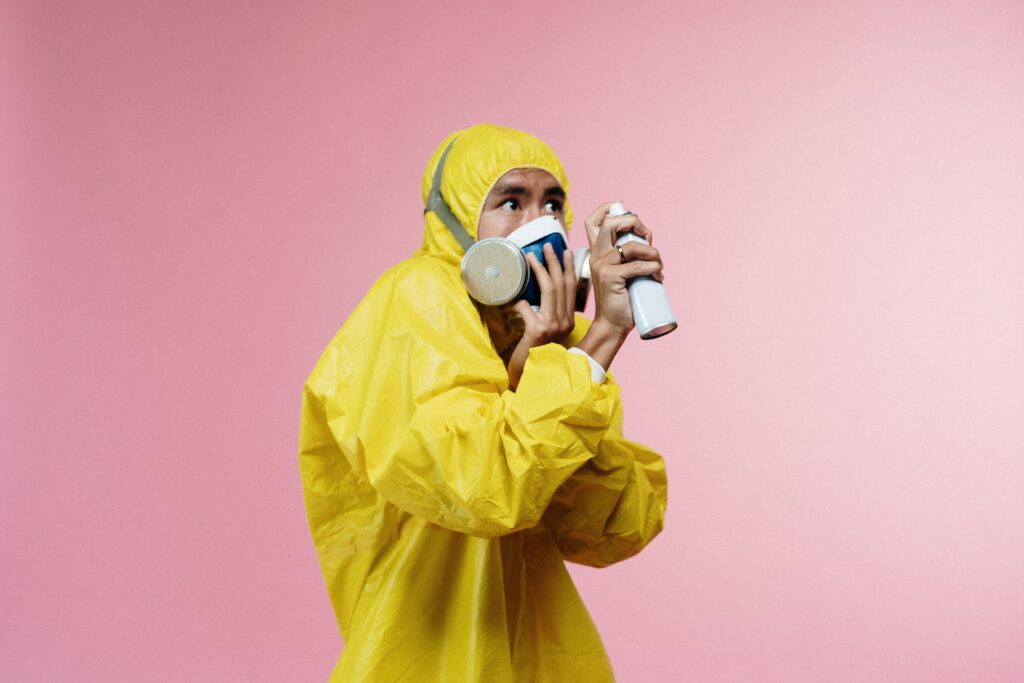

Continue to use surgical or FFP2 masks around infected people as respiratory droplets via coughing, sneezing or just spitting while talking (people do that, you know!) can spread the infection. Thoroughly disinfecting fomites will also help control the spread of infection.

On a greater scale we can avoid or reduce the number of pandemics by following certain mass guidelines

1) Stop deforestation– Deforestation leads to habitat loss of wild animals and forces them to wander into urban areas carrying all sorts of pathogens with them. So STOP ENCROACHING FORESTS!

2) Avoid or Stop Wild And Exotic Meat consumption– almost all of us already know the cost of eating bats, snakes, pangolins and any wild animal you can find. Wild and exotic animals are primary source of zoonotic pathogens. Continuing to do so will be the beginning to the exotic world of new pandemics.

3) Stop overuse of antibiotics in everything– Most of us think of bacteria as small feeble organisms that can be smitten out of existence. But they are very resilient, robust and easily adapt to their environment if required. Antibiotic abuse in people, agriculture and cattle has led to the rise of many drug-resistant bacteria or “superbugs” like Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). As we continue to overuse antibiotics we might as well be preparing for the next fortified Bubonic Plague (Black Death)

References

- Di Giulio, D. B. & Eckburg, P. B. Human monkeypox: an emerging zoonosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 4, 15–25 (2004).

- Wilson, M. E., Hughes, J. M., McCollum, A. M. & Damon, I. K. Human Monkeypox. Clin. Infect. Dis. 58, 260–267 (2014).

- Adalja, A. & Inglesby, T. A Novel International Monkeypox Outbreak. https://doi.org/10.7326/M22-1581 (2022) doi:10.7326/M22-1581.

- Wilson, M. E., Hughes, J. M., McCollum, A. M. & Damon, I. K. Human Monkeypox. Clin. Infect. Dis. 58, 260–267 (2014).

- Parker, S., Schultz, D. A., Meyer, H. & Buller, R. M. Smallpox and Monkeypox Viruses☆. Ref. Modul. Biomed. Sci. (2014) doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.02665-9.

- Grant, R., Nguyen, L. B. L. & Breban, R. Modelling human-to-human transmission of monkeypox. Bull. World Health Organ. 98, 638 (2020).

- Adler, H. et al. Clinical features and management of human monkeypox: a retrospective observational study in the UK. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 0, (2022).

Excellent post. I definitely love this site. Continue the good work!

Nice post. I learn something new and challenging on blogs I stumbleupon every day. Its always interesting to read content from other writers and use something from other web sites.

Everything is very open with a clear description of the issues. It was definitely informative. Your site is extremely helpful. Thanks for sharing!

Itís difficult to find experienced people for this topic, but you seem like you know what youíre talking about! Thanks